Gobekli Tepe is an ancient site that changed how people view early human history. The site is believed to have been built between 9600 BCE and 8200 BCE. For many years, the common consensus among historians and archeologists was that the rise of agriculture marked the beginning of humans creating large structures, buildings, and monuments. But the timeline of Gobekli Tepe contradicted the theory by providing evidence indicating that hunter-gatherer communities were already able to create massive stone structures before the rise of agriculture.

The Latest Discoveries On Site

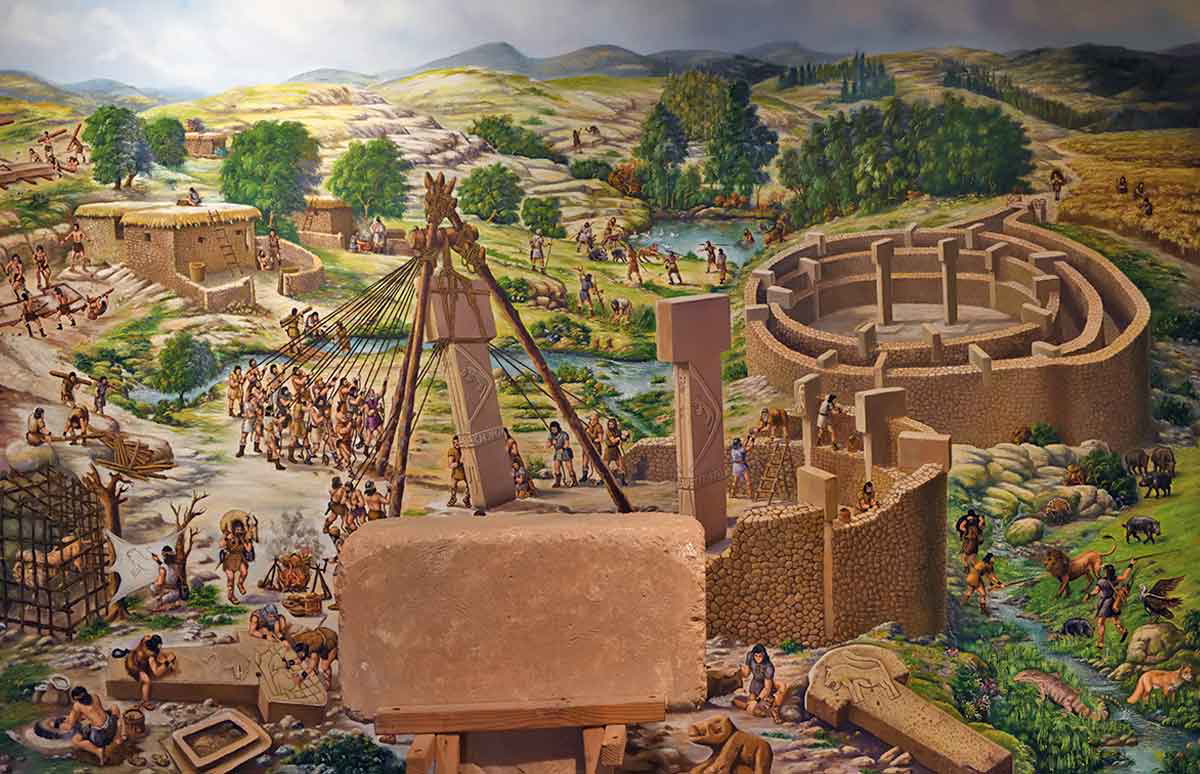

In recent years, sites have been discovered at Gobekli Tepe that feature domestic settlement structures, grain processing areas, and a rainwater collection system. The finding contrasts greatly with a previous view of the site which assumed that it was only a holy place used by hunter-gatherer communities, with few residents. The structures have for a long time been referred to as the world’s first temples and seem to have often collapsed and buried by natural calamities such as landslides, and later fixed. Notably, the designs and carvings are similar to those of other early sites such as Karahan Tepe.

That said, the site was first discovered in 1963 by archaeologists from the University of Istanbul and the University of Chicago during a joint survey, but the site was dismissed as an old cemetery. It was only in 1994 when German archaeologist, Klaus Schmidt, saw its importance and began excavations the following year. After he died in 2014, the work went on as a joint project of the German Archaeological Institute, Istanbul University, and Şanlıurfa Museum. Gobekli Tepe was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2018 due to its status as the oldest known temple complex in the world.

The oldest sections of the site, dated to around 9600 BCE, are currently linked to a pre-farming, early Neolithic group. Its tall T-shaped pillars, carved animals and the remains of ritual spaces thought to be the earliest in the world are seen as evidence of an advanced community. Interestingly, flint tools, stone carvings, and advanced construction methods were used by groups tied to the site.

The Unique Location of Gobekli Tepe

Gobekli Tepe is situated in south-eastern Anatolia in today’s Turkey near Şanlıurfa, about 9 miles northeast of the city. It sits on a hilltop in the Germuş mountain range and has huge stone pillars, with the biggest weighing about 50 tons. The huge pillars would have needed many workers and years of effort to carve and move. Carved from limestone, they were placed in circular layouts to supposedly form communal sanctuaries for rituals. Carvings of wild animals such as foxes, lions, and boars as well as signs of large feasts were found nearby.

The large stone pillars weighing many tons provided crucial evidence of collaboration. The fact that hundreds of workers would have been needed to build them was a clear indicator of teamwork among hunter-gatherers, likely guided by shared beliefs and social norms. Regarding the tall humanlike monoliths, they are believed to have been stylized to represent powerful beings or gods.

Carvings in Enclosures and on Pillars

Gobekli Tepe’s culture can be seen in the artistic style and symbolic carvings that feature prominently on its pillars. Many of the carvings featured animals such as foxes and lions which may have been linked to spirits or group symbols. Their exact meaning, however, is still unknown. Numerous versions appear at nearby sites and in later Levantine cultures.

Enclosure D, the oldest and most studied section of the site has a detailed layout with dozens of carvings, two central pillars, and benches along the walls. One of the most interesting discoveries about the site is that about 1,000 years after the enclosures were built, they were filled in with stone and debris. Scholars have long debated the reasons behind the practice. However, it is widely accepted that Gobekli Tepe was most likely a meeting point where hunter-gatherer groups came together. Its exact role though is still not fully understood.

The site’s last phase is dated to the Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic period and features smaller rectangular buildings and the final filling in of the larger enclosures. The act of deliberate backfilling is believed to have helped preserve the site for thousands of years. The site also seems to have been part of a wider network that included Nevalı Çori to the north and Jerf el Ahmar to the south in southeastern Anatolia, and northern Syria.