The allure of Indian textiles during the Victorian era was more than just fashion—it was a symbol of status, culture, and imperial dominance. As the British Empire crept at the edges of its borders, growing larger and ever stronger, so too did the fascination with the luxurious fabrics produced by Indian weavers and embroiderers. These fabrics became a staple of Victorian fashion, provided in a monopoly by the East India Company, and adored for their exotic appeal and unparalleled craftsmanship.

What Was the British East India Company?

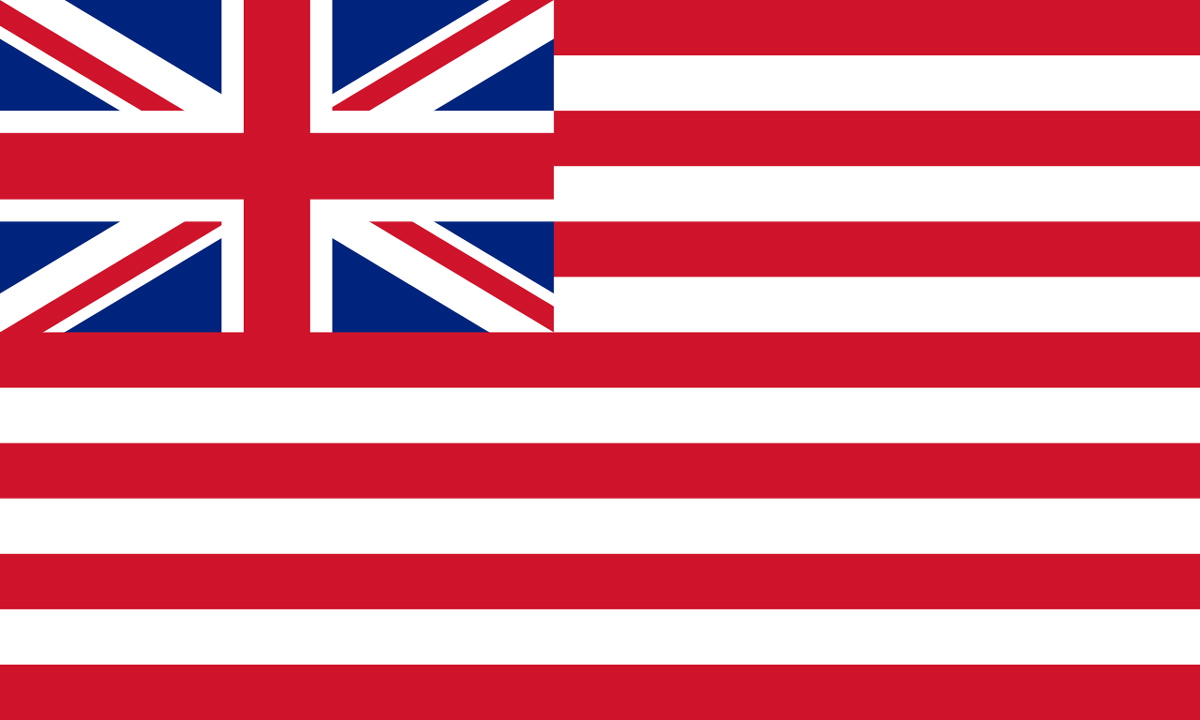

The East India Company, established in 1600 under the indomitable Queen Elizabeth, was not just a trading enterprise, it was a powerful force that shaped the economic and political landscapes of both Britain and India. Initially focused on the Silk Road spice trade, the company quickly expanded its reach to include the lucrative textile industry. Indian fabrics, known for their quality and intricate designs that were incredibly time-consuming for fabric artisans to produce, were in high demand in fashionable European circles. The company exploited this demand by establishing monopolies over guilds and individual artisans, often at the expense of the local culture and economy.

The East India Company’s control over Indian textile production and shipping allowed it to dominate the global market, exporting vast quantities of cotton, silk, and muslin to Britain. This trade not only enriched the company but also played a significant role in British ideas of superiority and the right to rule, contributing to the wealth and power of the empire all while the makers of the fabrics were heavily taxed and often bullied into not selling their goods to those who would buy them at market value.

Who Were the Indian Weavers and Embroiderers?

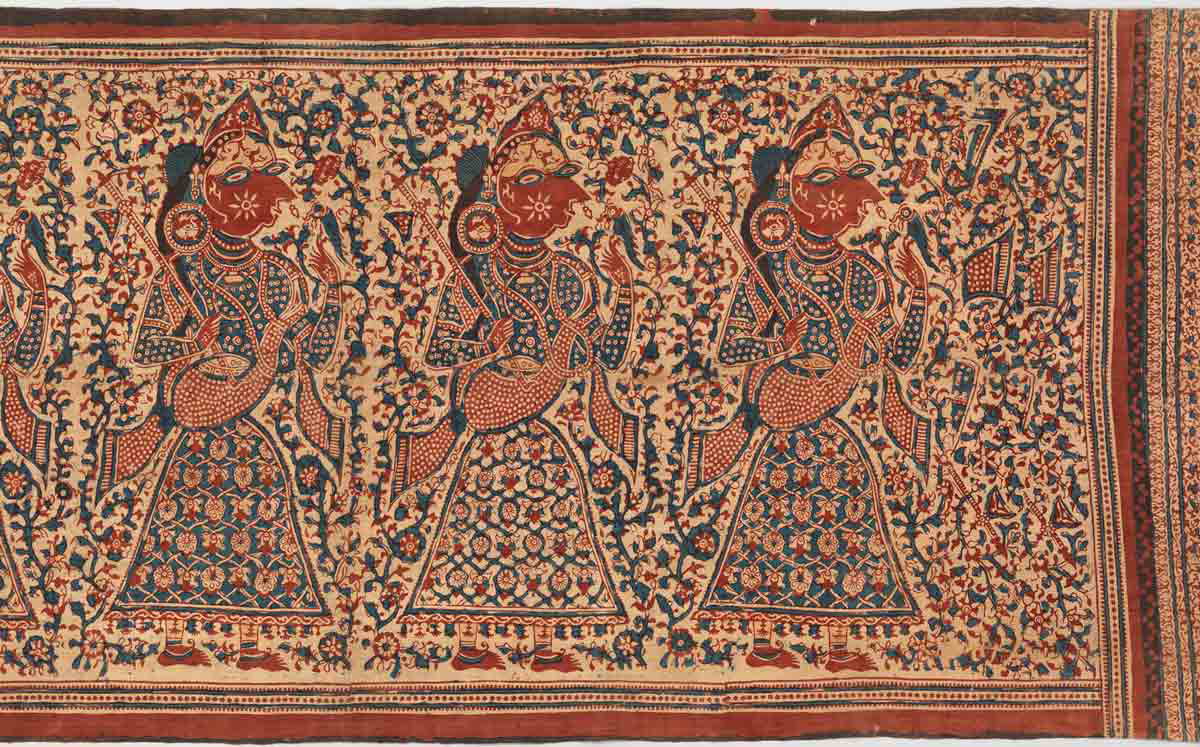

The East India Company’s (EIC) control over India deeply reduced the quality of life for the Indian weavers and embroiderers, who had long been revered for their exceptional skill. Each region in India boasted its own unique weaving traditions, with Gujarat on the West Coast emerging as a major hub of innovation for over five centuries. As Gujarati weavers migrated, they spread their intricate techniques across the subcontinent. From simple back-strap looms—made of sticks, rope, and a simple harness worn around the weaver’s waist—to complex draw-looms—capable of creating ikat blurs and patterned silks—these artisans were masters of their craft, a craft they had inherited from fathers and grandfathers who passed along trade secrets for generations.

The textiles they produced were not merely functional, they were works of art that demonstrated the wealth and power of India’s rulers before colonization as well as the rareness of the resources of the tropical monsoon climate. In the royal workshops of Gujarat, weavers crafted elaborate silks adorned with human, animal, and floral designs. These designs graced the nobility at the Mughal Court, a place where the East India Company first sent ambassadors to get the lay of the gem-like land. However, at this time India wasn’t a single unified thing but a collection of kingdoms and several princely states. The Deccan region was known for its meticulously hand-drawn and dyed cotton, used for courtly clothing and furnishings and finer than any produced elsewhere, while the Mughal imperial workshops produced lavish floral and figural wall hangings, often inspired by Chinese and Iranian designs.

Despite the artistry and skill involved, weavers and embroiderers faced severe exploitation under the East India Company. The EIC sought to police the global fabric trade, holding at bay other European kingdoms that had a foothold nearby. To do so, the EIC imposed oppressive conditions on Indian artisans. These craftsmen were often forced to sell their goods at extremely low prices while being burdened with heavy taxation.

In some cases, the EIC would even destroy looms and or cut fabric from the frames as they neared completion, ensuring the craftsmen remained dependent on the company. This exploitation led to a sharp decline in the traditional weaving industry and the lifestyle it had once afforded its artists, as the artisans struggled to survive in the face of the EIC’s viciousness.

The carving of printing blocks, another highly skilled practice, also suffered under the EIC’s dominance. Craftsmen at workshops turned rough cuts of wood into intricately carved printing blocks, a process requiring immense precision but one that made it possible for a pattern to be replicated again and again for a century or more. However, the English met this time-consuming craft with a process of their own with the rise of mechanization and the introduction of the Jacquard loom in the 19th century. Thus printed fabric became faster and less costly to make, resulting in traditional methods being increasingly sidelined and undervalued.

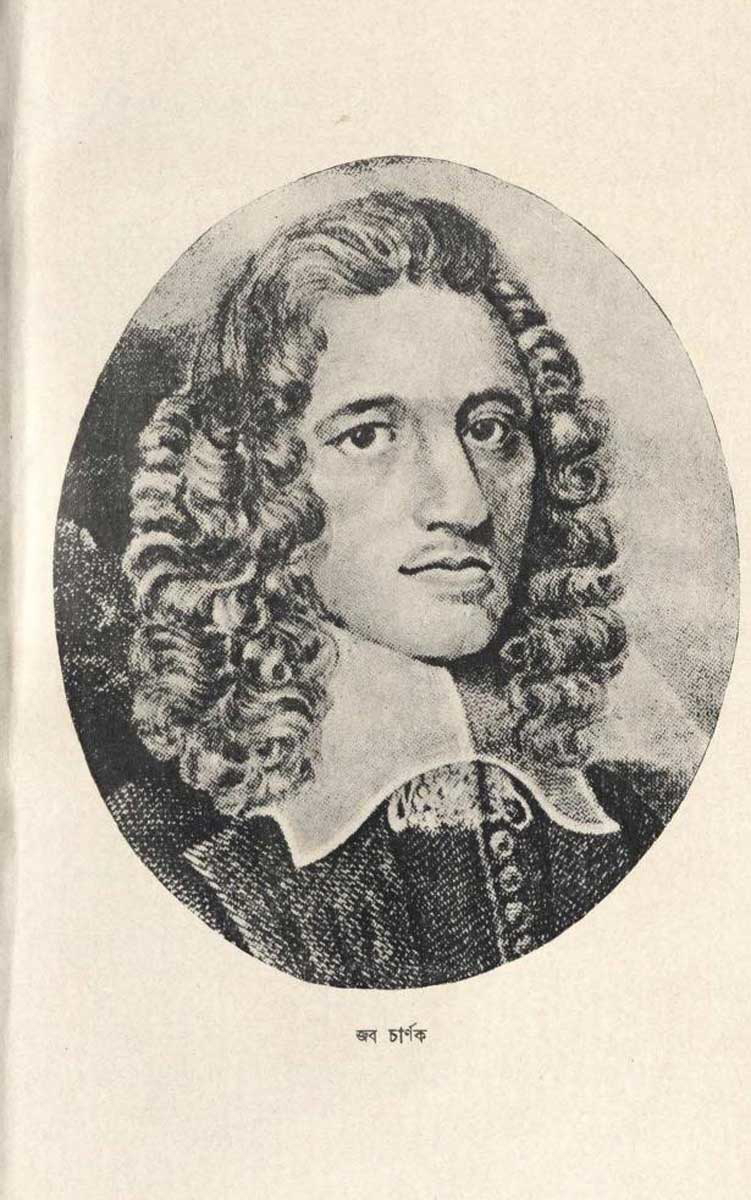

The impact of Indian textiles extended beyond European fashion—they played a crucial role in establishing connections between the British East India Company (EIC) and local communities. Marriage alliances were one such means of forging these connections. For instance, Job Charnock, a prominent member of the EIC, married an Indian woman named Maria, who greatly influenced his success.

Unlike many who looked down on the Indian natives and their traditions, Charnock adopted many local customs, including wearing Indian clothing and converting to Hinduism, which earned him respect within the community and eased trade negotiations. However, back “at home” in England, Charnock was derided for putting aside the privileges and honors of being a tried and true Brit. The influence of Indian women, like Maria, in shaping the fortunes of the EIC highlights the deep intertwining of culture, commerce, and craftsmanship during this period.

The EIC’s exploitation had devastating effects on India’s rich textile heritage. The demand for cheaper, mass-produced goods led to the decline of traditional weaving practices. Yet, despite these challenges, the legacy of Indian weavers and embroiderers endures, their skills preserved in the surviving museum pieces that continue to inspire awe for their artistry and craftsmanship.

Why Victorian Women So Desired Indian Fabric

Victorian women were captivated by Indian fabrics for several reasons, many of which stemmed from the limitations of textile production in England. The lightweight, breathable materials produced by Indian weavers were unmatched in their quality and comfort, especially compared to the heavier, coarser fabrics produced in Britain.

English mills simply couldn’t replicate the delicate muslins, luxurious silks, and finely woven cotton that flowed from Indian looms. No one who had been forced to wear itchy wool or rough homespun could compare the experience to donning India’s flowing, eye-catching fabrics. This made Indian textiles highly coveted by British women, who sought out these fabrics for their beauty, comfort, and exotic allure.

Beyond the fabric itself, Indian influences permeated nearly every aspect of Victorian society, reflecting the deep ties between Britain and its cash cow colony. The fascination with India could be seen in so very many aspects of English life, like the teas the landed gentry sipped and even the spices used in holiday cakes.

Indian textiles, especially the Kashmir shawl, became symbols of status and fashion in Britain. Since the mid-18th century, British women had worn these shawls to provide a touch of warmth over their short-sleeved, lightweight dresses. Over time, the Kashmir shawl evolved into a marker of respectability and taste, yet its high cost placed it well beyond the reach of all but the wealthiest tier of women.

In stark contrast to Britain, where sumptuary laws and written codes limited what was considered appropriate for those on different rungs of the social ladder to wear, Indian society had no such formal strictures. Instead, fashion norms were spread through word of mouth among India’s communities, allowing for a more fluid and diverse expression of style. This freedom, combined with the unmatched quality of Indian fabrics, made them even more desirable to British trendsetters.

The appeal of Indian textiles wasn’t just about their physical qualities—it was also about the cultural mystique they carried, representing a world that was both fascinating and nearly impossible to imagine in dreary England.

As Indian fabrics became more integrated into British fashion, they helped to shape a broader view of the world and people’s place within it, where the influences of the subcontinent were visible in everything from the patterns on a lady’s dress to the spices in her cupboard. This blending of cultures, for better or worse, spoke volumes about the complex and unequal relationship between Britain and India during the Victorian Era, where admiration for Indian artistry coexisted with the degradation of its people and resources.

The Peacock Dress and the Rise of the Anglo-Indian

The Peacock Dress, a now famous symbol of English wealth made in India and commissioned by Lady Curzon, epitomizes the fusion of British and Indian aesthetics during the British occupation of India. This opulent garment is celebrated for its intricate gold and silver embroidery and beetle wing-decorated feather motifs.

However, the true creators of this masterpiece—skilled Indian artisans in the very earliest years of the 20th century—are seldom acknowledged. These embroiderers, working under the constraints of colonial exploitation, were the unseen hands that crafted the fabric of the dress before it was sent for finishing at the House of Worth in France. Their artistry not only adorned the elite but also reflected the often exploitative dynamics between the colonizers and the colonized. Their stories remain largely untold, overshadowed by the dress’s illustrious European patron.

Much like each thread that makes up the peacock dress, Mary Wilson’s story is a poignant illustration of the racial and social complexities of the colonial era. Mary was born in India to her English father’s native, long-term paramour. However, as her father’s time in India came to an end, he decided Mary would make the trip back to an England she didn’t know to never again lay eyes on her mother or the country in which she had been born and raised.

As the illegitimate mixed-race daughter of Sir Henry Russell, a prominent British official in India, Mary was brought to England under circumstances that exemplify both the privileges and tragedies of her background. Her father refused to travel with her, instead requesting that a friend supervise her on a less well-appointed ship. She never stepped foot in her father’s stately home but was sent to a girls’ school.

Despite being educated and trained as a governess, Mary was kept at a distance from her father’s legitimate family, who seemed unaware of her existence. Henry Russell provided for her but never acknowledged her publicly, leaving Mary in a state of perpetual uncertainty about her identity and heritage. Mary remembered bits and pieces of her early life, asked questions about her mother and how she got to England and received only silence in response. Even when she was proposed to by an upstanding junior clergyman, the marriage negotiations were prolonged by her father refusing to claim her and her having nothing to write in the registry under her father’s name.

It should be noted that this marriage was considered largely above her position as an illegitimate governess but far, far below what Sir Henry Russell would accept for his legitimate, white daughters. The marriage did go through and was a resounding success that produced several children that identified as white including Amelia Selina, who was governess to Algernon Henry Barkworth, a first class passenger on the Titanic.

Mary’s experience parallels the plight of the Peacock Dress artisans: both were significant yet sidelined by the dominant historical narrative. Mary’s struggle to reconcile her origins with her social reality underscores the broader themes of exclusion and identity faced by mixed-race individuals during this period.

Mary Emmons, a woman from Calcutta who entered the historical records as a servant in his household but became the partner of Aaron Burr and mother to two of his children while his better-known wife, Theodosia, was dying, adds another dimension to this narrative. Like the artisans and Mary Wilson, Emmons’s contributions have been obscured by the more prominent figures in her life. Little is known about her journey to America or her personal experiences, despite her integral role in Burr’s household and her significant impact on his family. It is through her line, not that of Theodosia’s, that Aaron Burr’s descendants continue on. Yet, we don’t know what brought her from India to the new world, how she came to be in service, or even where she is buried.

Mary Emmons’ story highlights the often invisible roles played by women of color, particularly in mixed-race relationships or in servitude. Her life, much like those of the Peacock Dress artisans and Mary Wilson, reflects a broader pattern of historical erasure and undervaluation.

Victoria Becomes Empress of India

When Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1876, it marked the formalization of British rule over the subcontinent and the symbolic merging of British and Indian cultures. It also heralded the end of the East India Company, which had to cede control of the land to Victoria’s more morally brittle and staunchly upright authority.

This empresshood not only solidified Victoria’s position as a global monarch but also intensified the cultural exchange between Britain and India. Indian textiles, which had already been popular in Britain, became even more significant as symbols of the empire’s reach and influence. The Empress’s own wardrobe began to include more Indian-inspired garments, further popularizing these fabrics among the British aristocracy. Victoria’s fascination with India also led to the commissioning of Indian artisans to create textiles for the royal household, thus ensuring the continued prominence of Indian fabrics in British fashion.

It wasn’t just the lovely fabrics imported from India that Victoria admired. In June 1887, a weary and long-widowed Queen Victoria, then 68, met a tall, bearded young man in a scarlet tunic and snowy turban. Abdul Karim, just 23, knelt to kiss her feet, and Victoria somehow bonded with this wholly unusual young man. Karim had been sent from Agra as a human present to serve at the queen’s table and ease the way for some of her meetings with those in positions of influence in India. However, their connection quickly transcended the roles they were meant to play. Victoria, drawn to Karim’s presence, soon had him teaching her Urdu, elevating him from what some dismissively called a kitchen boy to her trusted “Munshi” or tutor.

Over the next 13 years, despite loud and race-fueled protestations, Abdul Karim remained by the Empress’s side, even accompanying her to her private cottage in the Scottish Highlands. While their bond was scandalous to the royal household it was maternal to the queen who had often failed to act with warmth toward her own children. Yet this friendship had more than just personal implications; it also left a lasting cultural mark. Karim introduced Victoria to Indian cuisine, notably serving her a meal of chicken curry, daal, and pilau, which she recorded in her diary with appreciation and set into the rotation of her favorite meals.

Victoria’s relationship with India went beyond her bond with Karim. Though she never visited India herself, she brought valued tokens of the country to her royal residences. The Queen-Empress had Indian attendants, wore Indian jewels like the vaunted Koh-i-Noor diamond, and even added a “Durbar Room” to Osborne House, filled with Indian art and display-worthy valuables. Victoria’s symbolic reign over India was thus marked by both her personal connections and her public displays of affection for the country.

Despite Victoria’s efforts to protect Karim, her fears of his mistreatment after her death were well reasoned. Her son and heir, Edward VII, quickly moved to erase Karim’s position, destroying the letters Victoria had written to him and sending him unhesitatingly back to India. However, the closeness between the Queen and her Munshi, immortalized in Victoria’s diaries and Karim’s own records, endures as a testament to this remarkable, if controversial, chapter in British colonial history.

Are There Still Specialty Indian Weavers and Embroiderers?

Despite the challenges posed by colonialism, the tradition of Indian weaving and embroidery has endured to the present day, though it has evolved over time. Today, there are still communities of weavers and embroiderers in India who practice their craft, often with a renewed focus on preserving historical techniques and regional patterns. Organizations and cooperatives have been established to support these artisans, providing them with the resources and fair trade markets needed to sustain their livelihoods.

While the global textile industry has shifted towards mass production, there remains a niche market for handwoven and truly one-of-a-kind Indian textiles, both within India and internationally. These artisans continue to produce fabrics that are celebrated for their quality, artistry, and cultural significance, ensuring that the legacy of the Indian textile industry endures despite the damage done to it during the British colonial period.